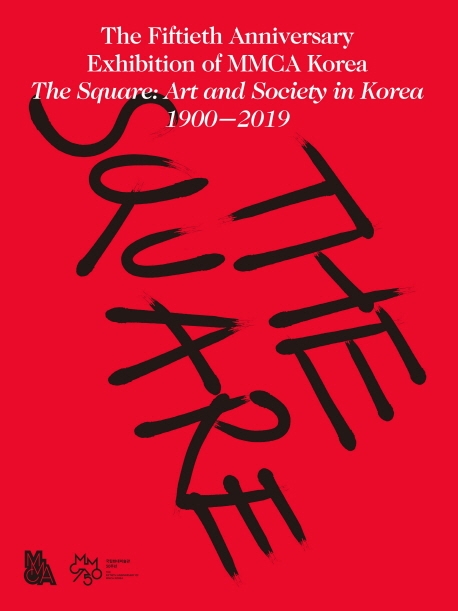

The Square: Art and Society in Korea 1900 -2019

광장: 미술과 사회 1900-2019 영문판

AUTHOR :

국립현대미술관

ISBN : 9791196777128

PUBLISHER : 국립현대미술관문화재단

PUBLICATION DATE :

December 24 ,2019,

SPINE SIZE : 1.6 inches

PAGES : 509

SIZE : 7.3 * 9.5 inches

WEIGHT : 3.2 pounds

CATON QTY : 1

PRICE : $

이 책은 국립현대미술관 개관 50주년 기념 도록 〈광장: 미술과 사회 1900-2019〉의 영문판이다. 국립현대미술관의 지난 50년의 기록을 글과 이미지로 담아 역사적 전시의 현장성을 생생하게 전달한다.

또한 2018년에는 충청북도 청주시 옛 연초제조창을 재건축한 국립현대미술관 청주를 개관하여 중부권 미술문화의 명소로 육성하고자 노력하고 있다.

국립현대미술관

1969년 경복궁에서 개관한 국립현대미술관은 이후 1973년 덕수궁 석조전 동관으로 이전하였다가 1986년 현재의 과천 부지에 국제적 규모의 시설과 야외조각장을 겸비한 미술관을 완공, 개관함으로써 한국 미술문화의 새로운 장을 열게 되었다. 1998년에는 서울 도심에 위치한 덕수궁 석조전 서관을 국립현대미술관의 분관인 덕수궁미술관으로 개관하여 근대미술관으로서 특화된 역할을 수행하고 있다. 그리고 2013년 11월 과거 국군기무사령부가 있었던 서울 종로구 소격동에 전시실을 비롯한 프로젝트갤러리, 영화관, 다목적홀 등 복합적인 시설을 갖춘 국립현대미술관 서울을 건립·개관함으로써 다양한 활동을 통해 한국의 과거, 현재, 미래의 문화적 가치를 구현하고 있다.또한 2018년에는 충청북도 청주시 옛 연초제조창을 재건축한 국립현대미술관 청주를 개관하여 중부권 미술문화의 명소로 육성하고자 노력하고 있다.

Held at MMCA Deoksugung, Part I considers the role and relationship of Korean art with the liberation movement during the Japanese colonial period. Considering the overall theme of how historical conditions influence the art of a given era, this part is divided into four sections: “Records of the Righteous,” “Art and Enlightenment,” “Sound of the People,” and “Mind of Korea.” “Records of the Righteous” recalls the individuals who found their own ways to bravely uphold the nation’s honor and autonomy during Japan’s initial encroachment into Korea and eventual colonial rule: literati scholars who vehemently asserted the need to maintain Confucian tradition and the isolationist policy; members of the resistance militia; people who risked everything to join the front line of the independence movement; people who chose to go into hiding to nurture future generations; and the martyrs who made the ultimate sacrifice by giving their life to the cause. Through Chae Yongshin’s magnificent portraits of these patriots, as well as their own excellent works of calligraphy and painting, this section looks back at how the thwarted dream of building an autonomous modern state led to resistance activities and dreams of enlightenment. This leads to the next section, “Art and Enlightenment,” which presents educational resources, illustrations from newspapers and magazines, and works by the Gaehwapa, a group dedicated to the reform and empowerment of Korea. Visitors can also trace the changing coverage of independence activities in art magazines published before and after the March 1st Movement of 1919. “Sound of the People” reviews how various international art trends were introduced through posters, magazines, and prints, while also examining Korea’s relations with global socialist and proletariat art movements. Notably, this section includes works by Pen Varlen and Yim Yongryun, two master artists who were exiled from their homeland due to colonial rule. Finally, “Mind of Korea” presents works by the pioneers of Korean modern art, such as Lee Qoede, Kim Whanki, and Lee Jungseob, showing how their passion for life and attitude towards art shone through their art, even during times of the darkest despair.

Although many of Korea’s first modern cities had public squares from the time of their establishment, the contemporary concept of the square had not yet arisen in this period. In the early twentieth century, the social and political role of the square was typically filled by the streets or marketplaces instead, where most people met and conversed. However, the artists and freedom fighters who resisted the loss of national sovereignty and struggled to enact a new era never abandoned the collectivism of a public space for the individualism of the back room. There were many possible paths between the back room and the square: some were narrow and winding, some were wide straight boulevards, while others led to a dead end. But no matter which path they chose, they were headed towards the ‘square’ of freedom and liberation, sharing the same vision of restoring Korea’s identity and autonomy.

Held at MMCA Gwacheon, Part II deals with the era of modernization, democratization, and globalization, from the Korean War to the present. Rather than a straight chronological presentation, this part has a mixed arrangement to allow for the intersection and coexistence of the back room, street, and square. To highlight the overarching theme of the exhibition, the title of each section is based on keywords from Choi Inhun’s novel The Square. In particular, this part invokes Choi’s symbolic and metaphorical use of color, especially black, gray, blue, and white. The displays are divided into a total of seven sections: six to the right of the main ramp and one to the left. The six sections on the right are “Blackened Sun”, “Han-gil(One Path)”, “Gray Caves”, “Painful Sparks”, “Blue Desert”, “Arid Sea” In addition, the right side includes a square dedicated to the May 18 Uprising in Gwangju. Finally, the section on the left is “White Bird,” a space for mourning and placing a wreath. Visitors are encouraged to move from right to left, following a roughly chronological path from the 1950s to the present with the square in the center.

Focusing on the 1950s, “Blackened Sun” begins with works by Jeongju An and Kang Yo-bae depicting wounds from the Korean War and the NorthSouth division. Next, “Han-gil(One Path)” explores how the rapid economic development of the 1960s was instigated by the military regime’s imperious push for progress and restoration, prioritizing national production at the expense of individual freedom and expression. By enforcing a uniform standard, the military government effectively denounced both the back room (individual freedom) and the square (autonomy of community). Featuring abstract works by Chung Kyu, Yoo Young-Kuk, and Kim Chong Yung, and experimental works by Kim Ku Lim and Lee Kun-yong, this section also includes separate corners for Yun Isang and Lee Ungno, both of whom were imprisoned for ideological conflicts. “Gray Caves” revisits the “gray” period of the 1970s, when Korea continued its incredible economic growth, even while suffering from extreme social oppression under the Yushin regime. In the novel The Square, the “gray cave” was a back room which became the only refuge where protagonist Yi Myeongjun and his lover Eunhye could hide. This period, when Koreans were forced to remain in the back room and could not enter the square, is represented by hyperrealist works, documentary paintings of the Vietnam War by military correspondent artists, and “Dansaekhwa” (“Korean monochrome”) paintings by Park Seo-Bo, Ha Chong Hyun, and Yun Hyong-keun.

“Painful Sparks” is based on a political gathering in a square filled with citizens fueled by the flaming desire for democratization. Thus, this section introduces the 1980s, the decade defined by the rise of Minjung art (“People’s art”) and the tight interweaving of ideology, politics, and culture. Notably, it was also in this period that the square came to be seen as the site for realizing the ideal of community, with a proliferation of group activities based on collective identities of class, nationality, and ideology. This spirit was evoked by poet Bak Chunseok in her book I Gathered in the Square, when she wrote, “In order to leave the square, I went to the square every single day.”1 Containing works by artists such as Shin Hak Chul, Kim Jung Heun, Lim Ok-Sang, Oh Yoon, Yun Suk Nam, and Bae Youngwhan, as well as Liberation of Work, a geolgae painting (hanging painting) by Choi Byungsoo, this section transfers an actual square into the museum. Meanwhile, artists Kang Honggu and Im Minuk used their works to disclose the social and structural contradictions that were hidden in the shadow of urban growth and economic development, even after the achievement of democracy.

Moving closer to contemporary times, “Blue Desert” covers the 1990s, while “Drought-colored Sea” takes us into the twenty-first century. First, the 1990s were the decade in which Korea leapt onto the international stage while initiating many profound domestic changes. Beginning from the 1988 Summer Olympics in Seoul, Korea successfully transitioned from a military government to a democracy, while also riding the wave of globalization. This wave made great ripples in the Korean art world, starting with the launch of the international art biennales in Gwangju and Busan in the mid1990s. A sharp increase in international art exchanges and communications helped many Korean artists enter the global spotlight. These developments corresponded to major social changes around the world, particularly the fall of the Soviet Bloc that began 1989 and the end of the Cold War, which brought on a global paradigm shift. Suddenly freed from its binary conflict with socialism, capitalism strengthened its hold on the world order and social structure. However, just a year after joining the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Korea suffered a crippling financial crisis that resulted in an IMF bailout in 1997.

Hence, the “blue square” (represented by the sea) that offered the last bastion of hope in the novel The Square no longer exists, having been replaced by a “Blue Desert” and a “Arid Sea.” The transition from a sea to a desert, and from blue to the color of drought, would seem to be a dark foreboding for the future, but signs of optimism can still be detected in works from these two sections. In the 1980s, the public square of Korea was filled with ideological protests and displays of defiance, but in the 1990s, many of those disputes fell by the wayside, enabling artists to focus on other issues. “Blue Desert” features works by the new crop of 1990s artists-such as Choi Jeonghwa, Lee Bul, and Ahn Sang-soo-who were part of the first Korean generation to experience the expansion of popular consumer culture and the liberation from ideological conflicts. Starting in the 1990s, more Korean artists began focusing on issues related to pluralization and the micro-oppression of daily life, showing an increased interest in human rights, social minorities (e.g., women, the disabled, immigrants, and homosexuals), and crises caused by neoliberalism and globalization (e.g., labor conditions, poverty, and the environment). This section contains works by Kim Youngchul and Lee Yunyop, who used their art to resist the cultural monopoly and empowerment of capitalism. In the “Drought-colored Sea” section, the shadow of fear and anxiety inherent to a post-capitalist society is cast over works by Kim Sunghwan, Im Heungsoon, Gimhongsok, and Kim Sora.

In the novel The Square, Yi Myeongjun is led to the “blue square” by two white birds-his lover Eunhye and their unborn child-who tragically die together. “White Bird,” the last section of Part II, is a memorial to the victims of Korean contemporary history, whether they met their fate in the back room, the street, or the public square. These victims include the comfort women; the expelled; independence activists; victims of the Korean War, the Vietnam War, and the May 18 Democratic Uprising; Miseon and Hyosun, who were killed by a US military vehicle; and finally, the unjustified and concealed deaths of the Sewol ferry. Perhaps these victims can experience a moment of healing by having their wounds tended by the works of Oh Jaewoo, jang minseung, Che Onejoon, and Nikolai Sergeevich Shin.

Finally, at MMCA Seoul, Part III confronts the here and now, addressing the contemporaneity of ourselves while simultaneously pondering the future significance of the square. Touching upon fundamental issues of the individual, community, and society, this part is organized along the following themes: I and the Other; portraits of community; the online square (time becomes space); changing communities; and the museum as the square. Presented in Galleries 3, 4, and 8, as well as in the hallway and outdoors, the works comprise various formats and media, including photography, video, performance, and even a collection of seven short stories, (also entitled The Square) written especially for this exhibition by seven writers.

In an era when anderheit (“otherness”) is supposedly dissolving, the portrait photographs of Oh Heinkuhn and Yokomizo Shizuka remind us of the unfamiliar experience of meeting and recognizing the Other. The people in the photographs remain inside their own private space-their back room- while the artists look at them from the street, the middle ground between the back room and the square. By maintaining such distance and refusing to form a mutually exclusive relationship, the photographers newly objectify their subjects, thus restoring anderheit.

Although many of Korea’s first modern cities had public squares from the time of their establishment, the contemporary concept of the square had not yet arisen in this period. In the early twentieth century, the social and political role of the square was typically filled by the streets or marketplaces instead, where most people met and conversed. However, the artists and freedom fighters who resisted the loss of national sovereignty and struggled to enact a new era never abandoned the collectivism of a public space for the individualism of the back room. There were many possible paths between the back room and the square: some were narrow and winding, some were wide straight boulevards, while others led to a dead end. But no matter which path they chose, they were headed towards the ‘square’ of freedom and liberation, sharing the same vision of restoring Korea’s identity and autonomy.

Held at MMCA Gwacheon, Part II deals with the era of modernization, democratization, and globalization, from the Korean War to the present. Rather than a straight chronological presentation, this part has a mixed arrangement to allow for the intersection and coexistence of the back room, street, and square. To highlight the overarching theme of the exhibition, the title of each section is based on keywords from Choi Inhun’s novel The Square. In particular, this part invokes Choi’s symbolic and metaphorical use of color, especially black, gray, blue, and white. The displays are divided into a total of seven sections: six to the right of the main ramp and one to the left. The six sections on the right are “Blackened Sun”, “Han-gil(One Path)”, “Gray Caves”, “Painful Sparks”, “Blue Desert”, “Arid Sea” In addition, the right side includes a square dedicated to the May 18 Uprising in Gwangju. Finally, the section on the left is “White Bird,” a space for mourning and placing a wreath. Visitors are encouraged to move from right to left, following a roughly chronological path from the 1950s to the present with the square in the center.

Focusing on the 1950s, “Blackened Sun” begins with works by Jeongju An and Kang Yo-bae depicting wounds from the Korean War and the NorthSouth division. Next, “Han-gil(One Path)” explores how the rapid economic development of the 1960s was instigated by the military regime’s imperious push for progress and restoration, prioritizing national production at the expense of individual freedom and expression. By enforcing a uniform standard, the military government effectively denounced both the back room (individual freedom) and the square (autonomy of community). Featuring abstract works by Chung Kyu, Yoo Young-Kuk, and Kim Chong Yung, and experimental works by Kim Ku Lim and Lee Kun-yong, this section also includes separate corners for Yun Isang and Lee Ungno, both of whom were imprisoned for ideological conflicts. “Gray Caves” revisits the “gray” period of the 1970s, when Korea continued its incredible economic growth, even while suffering from extreme social oppression under the Yushin regime. In the novel The Square, the “gray cave” was a back room which became the only refuge where protagonist Yi Myeongjun and his lover Eunhye could hide. This period, when Koreans were forced to remain in the back room and could not enter the square, is represented by hyperrealist works, documentary paintings of the Vietnam War by military correspondent artists, and “Dansaekhwa” (“Korean monochrome”) paintings by Park Seo-Bo, Ha Chong Hyun, and Yun Hyong-keun.

“Painful Sparks” is based on a political gathering in a square filled with citizens fueled by the flaming desire for democratization. Thus, this section introduces the 1980s, the decade defined by the rise of Minjung art (“People’s art”) and the tight interweaving of ideology, politics, and culture. Notably, it was also in this period that the square came to be seen as the site for realizing the ideal of community, with a proliferation of group activities based on collective identities of class, nationality, and ideology. This spirit was evoked by poet Bak Chunseok in her book I Gathered in the Square, when she wrote, “In order to leave the square, I went to the square every single day.”1 Containing works by artists such as Shin Hak Chul, Kim Jung Heun, Lim Ok-Sang, Oh Yoon, Yun Suk Nam, and Bae Youngwhan, as well as Liberation of Work, a geolgae painting (hanging painting) by Choi Byungsoo, this section transfers an actual square into the museum. Meanwhile, artists Kang Honggu and Im Minuk used their works to disclose the social and structural contradictions that were hidden in the shadow of urban growth and economic development, even after the achievement of democracy.

Moving closer to contemporary times, “Blue Desert” covers the 1990s, while “Drought-colored Sea” takes us into the twenty-first century. First, the 1990s were the decade in which Korea leapt onto the international stage while initiating many profound domestic changes. Beginning from the 1988 Summer Olympics in Seoul, Korea successfully transitioned from a military government to a democracy, while also riding the wave of globalization. This wave made great ripples in the Korean art world, starting with the launch of the international art biennales in Gwangju and Busan in the mid1990s. A sharp increase in international art exchanges and communications helped many Korean artists enter the global spotlight. These developments corresponded to major social changes around the world, particularly the fall of the Soviet Bloc that began 1989 and the end of the Cold War, which brought on a global paradigm shift. Suddenly freed from its binary conflict with socialism, capitalism strengthened its hold on the world order and social structure. However, just a year after joining the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Korea suffered a crippling financial crisis that resulted in an IMF bailout in 1997.

Hence, the “blue square” (represented by the sea) that offered the last bastion of hope in the novel The Square no longer exists, having been replaced by a “Blue Desert” and a “Arid Sea.” The transition from a sea to a desert, and from blue to the color of drought, would seem to be a dark foreboding for the future, but signs of optimism can still be detected in works from these two sections. In the 1980s, the public square of Korea was filled with ideological protests and displays of defiance, but in the 1990s, many of those disputes fell by the wayside, enabling artists to focus on other issues. “Blue Desert” features works by the new crop of 1990s artists-such as Choi Jeonghwa, Lee Bul, and Ahn Sang-soo-who were part of the first Korean generation to experience the expansion of popular consumer culture and the liberation from ideological conflicts. Starting in the 1990s, more Korean artists began focusing on issues related to pluralization and the micro-oppression of daily life, showing an increased interest in human rights, social minorities (e.g., women, the disabled, immigrants, and homosexuals), and crises caused by neoliberalism and globalization (e.g., labor conditions, poverty, and the environment). This section contains works by Kim Youngchul and Lee Yunyop, who used their art to resist the cultural monopoly and empowerment of capitalism. In the “Drought-colored Sea” section, the shadow of fear and anxiety inherent to a post-capitalist society is cast over works by Kim Sunghwan, Im Heungsoon, Gimhongsok, and Kim Sora.

In the novel The Square, Yi Myeongjun is led to the “blue square” by two white birds-his lover Eunhye and their unborn child-who tragically die together. “White Bird,” the last section of Part II, is a memorial to the victims of Korean contemporary history, whether they met their fate in the back room, the street, or the public square. These victims include the comfort women; the expelled; independence activists; victims of the Korean War, the Vietnam War, and the May 18 Democratic Uprising; Miseon and Hyosun, who were killed by a US military vehicle; and finally, the unjustified and concealed deaths of the Sewol ferry. Perhaps these victims can experience a moment of healing by having their wounds tended by the works of Oh Jaewoo, jang minseung, Che Onejoon, and Nikolai Sergeevich Shin.

Finally, at MMCA Seoul, Part III confronts the here and now, addressing the contemporaneity of ourselves while simultaneously pondering the future significance of the square. Touching upon fundamental issues of the individual, community, and society, this part is organized along the following themes: I and the Other; portraits of community; the online square (time becomes space); changing communities; and the museum as the square. Presented in Galleries 3, 4, and 8, as well as in the hallway and outdoors, the works comprise various formats and media, including photography, video, performance, and even a collection of seven short stories, (also entitled The Square) written especially for this exhibition by seven writers.

In an era when anderheit (“otherness”) is supposedly dissolving, the portrait photographs of Oh Heinkuhn and Yokomizo Shizuka remind us of the unfamiliar experience of meeting and recognizing the Other. The people in the photographs remain inside their own private space-their back room- while the artists look at them from the street, the middle ground between the back room and the square. By maintaining such distance and refusing to form a mutually exclusive relationship, the photographers newly objectify their subjects, thus restoring anderheit.

8 Youn Bummo, Director’s Foreword

12 Kang Seungwan, “On The Square: Art and Society in Korea 1900-2019”

Part I. 1900-1950

22 Kim Inhye, “The Role of Artists in Times of Darkness”

27 1. Records of the Righteous

29 Choi Youl, “The Struggle of Symbols: The Patriot’s Soul and the Flame of Modern Times”

65 2. Art and Enlightenment

67 Kim Mee Young, “Challenge and Resistance: Korean Art and Culture after the March 1st Movement until the 1930s”

111 3. Sound of the People

113 Hong Jisuk, “Ideology and Development of Korea’s Proletarian Art Movement in the Japanese Colonial Period”

159 4. Mind of Korea 161 Kim Hyunsook, “The Trajectory of the Paintings Presenting Joseon”

Part II. 1950-2019

196 Kang Soojung, “The Square: Art and Society in Korea 1900-2019 Part II. 1950-2019: Opposing Chronic Historical Interpretation Syndrome”

209 Kwon Boduerae, “The Public Square Set Forth in The Square: Firm Individuals and Flexible Community”

215 1. Blackened Sun

231 2. Han-gil (One Path)

241 3. Gray Caves

257 4. Painful Sparks

275 Shin Chunghoon, “In Search of a Language of Necessity: Korea’s Art Discourses during the Second Half of the Twentieth Century”

287 Kim Hak-lyang, “The Draft of Monsters Biography in Modern and Contemporary Korean Art: “Jungmi [精美; Clean and Pure Beauty]”, Abstraction, Hangukhwa[Korean Painting], Minjung Art, and Fine Art?”

299 5. Blue Desert

313 6. Arid Sea

325 Chung Dahyoung, Lee Hyunju, Yoon Sorim, “Applied Art: The Zone of Criticism Sparked by Craft, Design, and Architecture”

333 7. White Bird

343 Kim Won, “Memory, Erasure, and Their Complicity: Forgotten Ghosts and Their Representation”

Part III. 2019

354 1. I and the Other

355 Lee Sabine, “The Square, 2019”

393 Yang Hyosil, “The Square: Emergence of Bodies and Politics of Art”

400 Lim Jade Keunhye, “New Discourses on Art Museums as the ‘Square’”

409 2. Museum, Square and Theater

410 Sung Yonghee, “Is the Public Square Possible?”

419 Lee Kyungmi, “The Evaporation of the Real and the Creation of a Nonconforming Theater Space”

425 The list of works for the exhibition

455 The list of artists for the exhibition

459 Glossary

465 Installation View

12 Kang Seungwan, “On The Square: Art and Society in Korea 1900-2019”

Part I. 1900-1950

22 Kim Inhye, “The Role of Artists in Times of Darkness”

27 1. Records of the Righteous

29 Choi Youl, “The Struggle of Symbols: The Patriot’s Soul and the Flame of Modern Times”

65 2. Art and Enlightenment

67 Kim Mee Young, “Challenge and Resistance: Korean Art and Culture after the March 1st Movement until the 1930s”

111 3. Sound of the People

113 Hong Jisuk, “Ideology and Development of Korea’s Proletarian Art Movement in the Japanese Colonial Period”

159 4. Mind of Korea 161 Kim Hyunsook, “The Trajectory of the Paintings Presenting Joseon”

Part II. 1950-2019

196 Kang Soojung, “The Square: Art and Society in Korea 1900-2019 Part II. 1950-2019: Opposing Chronic Historical Interpretation Syndrome”

209 Kwon Boduerae, “The Public Square Set Forth in The Square: Firm Individuals and Flexible Community”

215 1. Blackened Sun

231 2. Han-gil (One Path)

241 3. Gray Caves

257 4. Painful Sparks

275 Shin Chunghoon, “In Search of a Language of Necessity: Korea’s Art Discourses during the Second Half of the Twentieth Century”

287 Kim Hak-lyang, “The Draft of Monsters Biography in Modern and Contemporary Korean Art: “Jungmi [精美; Clean and Pure Beauty]”, Abstraction, Hangukhwa[Korean Painting], Minjung Art, and Fine Art?”

299 5. Blue Desert

313 6. Arid Sea

325 Chung Dahyoung, Lee Hyunju, Yoon Sorim, “Applied Art: The Zone of Criticism Sparked by Craft, Design, and Architecture”

333 7. White Bird

343 Kim Won, “Memory, Erasure, and Their Complicity: Forgotten Ghosts and Their Representation”

Part III. 2019

354 1. I and the Other

355 Lee Sabine, “The Square, 2019”

393 Yang Hyosil, “The Square: Emergence of Bodies and Politics of Art”

400 Lim Jade Keunhye, “New Discourses on Art Museums as the ‘Square’”

409 2. Museum, Square and Theater

410 Sung Yonghee, “Is the Public Square Possible?”

419 Lee Kyungmi, “The Evaporation of the Real and the Creation of a Nonconforming Theater Space”

425 The list of works for the exhibition

455 The list of artists for the exhibition

459 Glossary

465 Installation View